Parsing Lonergan’s Law of the Cross: Might We Abstract a Dispensatory Lex Crucis from Lonergan’s Concessive Lex Crucis?

There are some types of pain and certain degrees of suffering, all metaphysically unavoidable, that needn’t necessarily be considered disproportional to divine theophanic & theotic ends. Those pains & sufferings could indeed have been divinely intended as instrumental means. These instrumental pains & sufferings would ensue from such primordial protological distancings, both epistemic & axiological, as would be indispensable to the gifting of a meaningful degree of freedom to finite rational creatures. They would be teleologically ordered, then, toward the epistemic & axiological closures of theosis, so as one of many other pedagogical means.

This is not to deny that there could be other pains & sufferings that, although both remediable & transformable, would still be considered as merely accidental & only divinely permitted. These accidental pains & sufferings would ensue from moral evil, whether meta-historically & angelic and/or historically & human.

The divine will would thus be operating in various providential contexts of not only the good (e.g. cosmic deifications as ends) and dispensatory (e.g. maturation processes as primary means), but also the concessive (anticipatory modal remedies as secondary means)?

Abstractly, regarding the logical problem of evil, then, it suffices to generally acknowledge that some types of pain and certain degrees of suffering could be divinely intended as protologically dispensatory, some permitted as meta/historically concessive.

All types of pain and degrees of suffering would necessarily be remediable & all moral evil will necessarily be vanquished, i.e. none everlastingly permitted as that would prima facie be a disproportional consequence.

Concretely, regarding the evidential problem of specific pains, sufferings & evils, we best maintain a respectful silence regarding which are dispensatory and which concessive (including how & why), while entrusting all to Providence. Otherwise, we risk trivializing the enormity of human pain & immensity of human suffering.

Put differently, I believe that specific types & certain amounts of pain & suffering may well be divinely intended to play instrumental roles in advancing divine theophanic & theotic ends. They could, for example, facilitate our closures of epistemic distancing, working with our gifts of nescience, faith & trust as one (among other) pedagogical means by which God calibrates our desires in order to proportionately titrate His intimacy via progressive revelations.

As for those types & amounts of suffering that would be evil, e.g. disproportional, those would never ever be divinely intended and under no circumstances would ever play any instrumental role as means to divine ends. That’s not to deny that their effects could be transformable & indeed must be conquerable. It’s only to insist that they are necessarily possible, metaphysically, as unavoidable accidents, which are only ever divinely permitted precisely because they are absolutely remediable.

Because no eye’s seen, ear’s heard or heart’s conceived what’s been prepared, eschatologically, we’re in no position, historically, to measure the weight of eternal glories so as to assess the proportionality of life’s various pains & sufferings. So, rather than proffer specific evidential theodicies, which run the risk of trivializing the enormity of human pain & immensity of human suffering, we must, at least, retreat to mere logical defenses, which address, only in the most general way, the divine permission of the necessary possibility of accidental – never instrumental – evils. Those defenses, for me, would include various free will & autonomy defenses, soul-crafting & epistemic distancing, also Behr’s death as divine pedagogy.

Eschewing evidential theodicies & even going beyond logical defenses, I’m personally willing to agnostically bracket which side of the pain & suffering proportionality divide that even death falls on. More basically, like Dame Julian, I’m content with Tolkien’s estel, which grounds my hope in trusting Jesus as Abba’s character witness.

Whatever God may ultimately be responsible for, we can have the confident assurance that there’s absolutely no moral culpability in play.

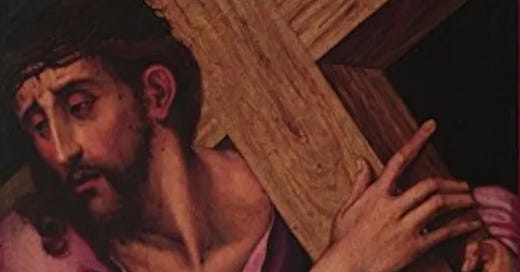

I raise these issues in conjunction with a consideration of Lonergan’s Law of the Cross. Few soteriological accounts are as coherent as Lonergan’s notion of redemptive justice, which he calls the justice of the cross. “This justice was about absorbing evil and transforming it into good. About persevering in love, gratitude, wonder, no matter what. About choosing a difficult good,” writes Ligita Ryliškytė, SJE.

Ryliškytė explains that “the justice of the cross regards, not retributive justice, but the possibility of justice among sinners. This possibility, it is argued, is inaugurated by Christ’s transformation of suffering into the means of a new finality in history, the probabilities of which are decisively shifted in the cross event and concretely realized through the emergent agape network, the higher integration of the human good of order through the whole Christ, head and members, by the power of the Holy Spirit.”

This Lex Crucis account well addresses how the divine concessive will remedies divinely permitted accidental evils (whether historical or meta-historical).

What I propose for your reflection is whether, beyond this Concessive Lex Crucis, in conformity with both the primacy of Christ, theologically, and our primordial protological distancings, anthropologically, might we be able to parse out & articulate, additionally, a more basic Dispensatory Lex Crucis?

I see a fruitful avenue for this exploration in a consideration of how Lonergan uses “dialectic” in a twofold sense.

Ryliškytė observes that, in Robert M. Doran’s terms, “there is the dialectic of contraries and the dialectic of contradictories. As implied in Lonergan’s utterance that ‘dialectic denotes a combination of the concrete, the dynamic, and the contradictory,’ only the dialectic of contradictories is dialectic in a proper sense. The dialectic of contraries, strictly speaking, concerns development, that is, a successful negotiation of the tension between finality and limitation. The tension between intersubjectivity and practical common sense, and even the emergence of physical ills, to give a few examples, result from the dialectic of the contraries. However, when the polymorphism of human consciousness and moral impotence step in, the dialectic of the contraries easily turns into the dialectic of contradictories, where self-transcendence is opposed by the situation of evil, that is, the objective surd (inasmuch as it has being). The fundamental dialectic between evil and good enters the scene.”

Consistent, then, with a harmonizing ontology & our putative Dispensatory Lex Crucis, our primordial distancings would be integral to our indispensable developmental & maturation processes, so sophiological. A dialectic of contraries would refer to our theotic negotiatons of our radical finitude as situated in infinite potency to the divine. Any historical pains & sufferings attendant thereto would be instrumental & divinely intended but proportional, eschatologically, to theotic & theophanic ends. From our present perspective, because neither eye’s seen nor ear’s heard nor heart’s conceived those ends, beyond mere foretastes, evidential theodicies are of no avail.

Lonergan’s soteriological Concessive Lex Crucis engages the fundamental dialectic between evil and good or the dialectic of contradictories, which I believe we might more aptly refer to as the dialectic of subcontraries.

If, per Lonergan’s soteriological Concessive Lex Crucis, the intrinsic intelligibility of redemption is the transformation of evil into good, then, more fundamentally, per an original sophiological Dispensatory Lex Crucis, the intrinsic intelligibility of theosis is transformation of all pains & sufferings into good, the noncoercive closings of original epistemic & axiological distancings of all finite rational creatures, who’ll everlastingly remain in infinite potency to the divine.

My twist, above, on Lonergan’s Lex Crucis is intended to be explicitly consistent with Bracken’s Neo-Whiteheadian systems-oriented approach to the God-world relationship as set forth in his Divine-Human Intersubjectivity and the Problem of Evil, Open Theology 2018; 4: 60–70.

Similarly, it resonates with Jack Haught’s aesthetic teleology, wherein, despite our ontological ruptures located in the past as could have given rise to all manner of evil, many of creation’s pains & sufferings may otherwise be integral to our teleological strivings oriented to the future.

It is particularly meant to advance the wisdom of Tom Belt’s participatory account of the Lex Crucis: “Christ can be said to take our shared humanity to the abyss of the Void and there face our finitude and mortality under the conditions of our own violence, not so that we need not face the Void and die there, but because we must, and so that we may do so without falling into despair and misrelation (Heb 2:14).”

https://afkimel.wordpress.com/2018/10/22/the-cross-substitution-participation/

Finally, it is meant to reflect Fr John Behr’s theoanthropology as engaged by Tom Belt.

https://afkimel.wordpress.com/2025/02/24/j-r-r-tolkien-and-the-unnaturalness-of-death/#comment-45178

As Merton observed [paraphrasing from memory], our faith in God does not mean that we shall never suffer. Being a Christian, in some circumstances, can even make our suffering more likely. Our faith in God does mean, however, that evil shall never become the worst.

See