Responses to Fr Rooney’s Church Life Journal Series on Indicative Universalism

See these articles:

https://churchlifejournal.nd.edu/articles/authors/james-dominic-rooney/

Please also see:

Why Beatific Contingency is an Oxymoron – about our divine indwelling

Parallels between Logical & Evidential Problems of Evil & of Hell

The Full Maximian Apokatastases Monty: immortality, theotic realization & apokatastenai

a storyboard regarding the “hows” of apokatastenai

The Incoherencies of Hard Universalism By James Dominic Rooney October 18, 2022

FrJDR writes: Let us be clear about our terms. Universalists think that all will be saved. Universalists are not saying that everyone will end up in heaven just by good luck; people who believe in the possibility of hell can believe that.[1] Universalists instead want to argue that it is not possible for anyone to end up in hell for eternity. Many defenders of universalism assert God would not be good if he allowed even the possibility of hell. More technically, then, universalists hold that it is a necessary truth that all are saved. This sets universalists apart from theologians like Hans Urs von Balthasar or Jacques Maritain who thought we might legitimately hope and pray that all people end up saved. These theologians are not universalists—although they are sometimes called “soft universalists”—because they held it was possible for people to end up in hell, and their views would not be implicated in what I am going to argue against, which is sometimes called “hard universalism.”

If it is a necessary truth that all will be saved, something makes it so. The only way it would be impossible for anyone to go to hell is,

That God could not do otherwise than cause human beings to love him or

That human beings could not do otherwise than love God.

There is no third option.

Both of these options, however, entail heresy. This is why universalism has been seen as heretical by mainstream Christianity for millennia, for good reason.

John’s response:

If it is a necessary truth that, eternally, none will be – not only not consciously tormented, but – either deprived of their original beatitude or foreclosed upon in their original teloi, then something makes it so.

God would not be good if he allowed even the possibility of eternal conscious torment, eternal deprivation of original beatitude or eternal foreclosure of original teloi, because without sufficient knowledge of God a finite creature could not definitively reject God and with a sufficient knowledge of God a finite rational creature would be gifted, along with impeccability, at least a love of God for sake of self. Divine punishments that would permit the eternal suffering of finite creatures are prima facie disproportionate. God would not be good if he allowed even the possibility of such disproportionate punishments.

1) the possibility of eternal conscious torment – This conception is being softened even by many perditionists nowadays?

2) eternal deprivation of original beatitude – Maritain entertained the possibility of a post-mortem universal restoration of original beatitude. Many perditionists properly recognize a limited array of universally enjoyed beatitudes.

3) eternal foreclosure of original teloi – Universal hylomorphism blocks this inference. Sin does parasitize our theotic processes & vicious habits do situate between our volitional potencies & acts. While such sinful habits can hinder our reductions of those potencies, they can never utterly obliterate them. While they can obscure our essential nature as imagoes Dei, they can never wholly eclipse it.

4) without sufficient knowledge of God a finite creature could not definitively reject God – Call it circular. Call it tautological. It doesn’t make it not true. It’s still more taut, existentially & evidentially, than competing accounts, which are absurdly implausible.

5) with a sufficient knowledge of God a finite rational creature would be gifted, along with impeccability, at least a love of God for sake of self – This is boilerplate post-mortem anthropology vis a vis Thomistic concepts like predestination, impeccability & inancaritability.

6) punishments that would permit the eternal suffering of finite creatures are disproportionate - Prima Facie.

7) the possibility of such disproportionate punishments – Per a cooperation with evil and double effect-like calculus, when such a disproportionality is in play, permission becomes tantamount to intent. This dynamic is related to DBH’s game theoretic analysis and the moral modal collapse at the eschatological horizon.

The above is not so much a rejection of the characterization that indicative universalism entails believing that “it would be impossible for anyone to go to hell.” It’s a rejection of popularized conceptions of hell that would make it more than a transient purgatorial state for any given rational creature. So, I reject perditionist definitions because, in my view, they don’t even refer.

As for these options:

That God could not do otherwise than cause human beings to love him or

That human beings could not do otherwise than love God.

These are too facile. They fail to distinguish between divine necessity and fittingness, between human erotic & agapic loves and other considerations that will be in play, below.

######

FrJDR writes: In any event, it seems to make perfectly good sense (“meaningful”) to say God could have done otherwise than create the universe, or that God did not need to become incarnate.

John’s response: Creation & grace are utterly gratuitous.

######

FrJDR writes: What is necessary is that God could have done otherwise, which is precisely what Hart rules out when he draws the heretical conclusion that “creation inevitably follows from who [God] is.”

John’s response: I only ever gathered from Hart that he was talking in terms of fittingness not necessity.

######

FrJDR writes: Because denying God’s freedom is serious, universalists typically focus instead on undermining human freedom. David Bentley Hart in his That All Shall Be Saved is, again, a good example. His two strategies for defending that everyone necessarily will be saved are, first, that the notion of mortal sin is somehow logically contradictory, so that making a choice to turn away from God eternally would be choosing completely arbitrarily, without reason, and contrary to all reason. Second, he argues that God’s love and benevolence would be incompatible with hell, because no possible reason can be given on which God neither intends the suffering of the damned for its own sake nor as a mere instrumental means for some other good.

John’s response: The above pretty much reduces to my own conclusions, above, first regarding the incoherency of putative definitive rejections of God and also regarding a moral modal collapse where permission becomes tantamount to intent when disproportionate evils are in play:

######

FrJDR writes: If culpable negligence is real, then it seems to me there is no ground to argue the concept of mortal sin entails a contradiction. You do not need to have God’s own knowledge to know “well enough” that something is wrong.

John’s response: While we can and do know “well enough” that many things are wrong, our knowledge of what’s really good rather than only apparently good grows and, along with it, our degree of culpability. Universalists needn’t deny this. Rather, we argue we don’t have a sufficient degree of knowledge to be absolutely culpable.

######

FrJDR writes: Logically speaking, I would argue that you only need three truths to get you to the possibility of hell: People can want things that do not correspond to what they ought to want (and do not necessarily or naturally want to love God) Learning new facts about the world, God, or yourself need not change what you want. God does not need to change what you want. By your free choices then You can choose to love things that orient you away from God and your true source of happiness in him. Then, even given an infinite time, there is no necessity that you learn anything new about yourself or the cause of your suffering that would make it impossible for you to do anything else except love God. This is to affirm that humans are free. A person does not need to act on any one set of reasons they have available to them, but can always reconsider the reasons for which they act. Nothing outside of them necessitates their choices (i.e., which reasons they act upon).

John’s response: Regarding “Learning new facts about the world, God, or yourself need not change what you want.” – Astute Thomists are aware that eschatological realities like predestination, impeccability & inancaritability present perditionists with a universalism problem on precisely this point. There are no character or disposition-based beatific contingencies. For those who reject a concrete (not abstract) natura pura, there are no indwelling-based beatific contingencies, either. A truly efficacious grace is infallibly followed by the act to which it tends, e.g. contrition. Even before one’s will consents to it, that grace, infallibly sure of success, will infallibly procure one’s consent, produce that act – of contrition. While it infallibly procures one’s consent, it doesn’t necessitate consent, instead leaving one free to dissent. The will will infallibly say "yes" to it, but it is free to say "no.”

######

FrJDR writes: And, similarly, God is under no obligation to break you out of this state, so you could persist in it forever.

John’s response: Again, more astute Thomists … … …

######

FrJDR writes: Further, if Hart’s argument were right that we could not rationally choose anything opposed to God, who is in fact the Good himself, this would mean everyone possesses supernatural love of God necessarily, since that love just consists in having God as our chosen end. Obviously, if we could not stop loving God, there would be no need for Christ’s Passion, the sacraments of baptism or penance, and so forth, because everyone would necessarily be in a state of grace. For many reasons, then, this first strategy of arguing that mortal sin is incoherent relies on plausible-sounding claims which, when examined, turn out to be unsound.

John’s response: Here, I find it helpful to frame this reality in terms of degrees akin to Ignatian Humility and Bernardian Love, including such distinctions as between an erotic love of God for sake of self coupled with imperfect contrition and an agapic love of God for sake of God coupled with perfect contrition. A Thomistic Autonomy Defense of Evil (not hell) would cohere well with our theotic ends of divine intimacy, such as an agapic love of God for sake of God as coupled with perfect contrition & continuing in eternal epectasy. The graces flowing from the divine economy would remain ever efficacious in overcoming sin & death and fostering our co-self-determined growth in divine likeness. Why must one’s conceptions of freedom, autonomy and the efficacy of grace be necessarily tied to a violent dichotomy between hating God, on one hand, and divine nuptial bliss, on the other? What’s incoherent about creation, incarnations and grace being peacefully & harmoniously ordered, rather, toward our journeys from abundance to superabundance, from divine images to likenesses, from friends to lovers, from enlightened self-interest to agapic self-emptying?

######

FrJDR writes: Traditionally, orthodox Christians have argued that God merely permits moral evil, such as hell, rather than intends it either as a good in itself or as an instrumental means for achieving something good. God allows moral evil—as John Damascene does in Book II and III of his Exposition of the Orthodox Faith—because God wants free creatures, as only free creatures can be in relationship with him. The reality of creatures who are really free entails the possibility of moral evil.

John’s response: While I ultimately rely on my trust relationship with God as enhanced by the special revelation of Abba in Jesus, apart from either logical defenses or evidential theodicies, both the free will & autonomy defenses ordered toward divine intimacy are eminently reasonable to me.

######

FrJDR writes, after an inapposite disquisition on DBH’s arguments: Creatures would not be free if they were necessitated to act in some specific way. God’s omnipotence does not extend to doing things that are nonsensical, and a necessitated free person is a contradiction in terms.

John’s response: There’s nothing in DBH’s stance, however, that’s inconsistent with a non-necessitating, efficacious grace infallibly followed by an act of contrition and sure of purgative success.

######

FrJDR writes: Hell is a product of our free choices, not God denying us something we need or pushing us down that path. There is then nothing about God’s plan for creating free people, even when God knows that we will reject his love, that means he is causing or desiring that we reject him. While metaphysically accurate, such responses can be unconvincing. God looks cruel if he creates human beings just to be damned. Hart’s claims that God must be “all-in-all,” victorious over evil, and comprehensibly the supreme Good is merely to say God must have a suitable justification for permitting hell. What is missing in response to Hart’s second strategy is a convincing justificatory reason God might have for permitting hell that is compatible with his goodness. We know in general that God only allows evil because he can produce out of it some greater good. Even for Hart, natural and moral evil would need to be allowed by God, and God does not desire to inflict suffering upon anyone even if he permits it for some good reason. But, if this is true, then there is no principled logical reason that God cannot have a good reason to allow even that moral evil that leads to damnation. I cannot see how we can know that God would not have such a good reason—God’s reasons and omnipotence are far beyond our comprehension. If we merely stick to logic, there is nothing contradictory here: we should broadly conclude God permits the possibility of damnation only because God loves us and wills our good. Whatever those reasons are in particular, God does “not desire the death of the wicked but that the wicked turn from his way and that he live” (Ezek 33:11).

John’s response: The problem with “If we merely stick to logic, there is nothing contradictory here,” is that the theological skepticism of the perditionist regarding the problem of hell and that of the theodicist regarding the problem of evil are invoking radically disproportional evils in their respective mysterian appeals, the latter evil being, although otherwise horrendous & incomprehensible, finite and transitory, the former infinite and everlasting. The divine permission of transient evils, generally considered, already challenges everyone’s belief in some measure, although our unbelief can be greatly mitigated by the weight of eternal glories promised. If a divine permission of everlasting evils for finite creatures remains unconvincing, perhaps it’s mere logical possibility is not even worthy of belief since it even more egregiously, i.e. to an absolute extent, violates our parental instincts, aesthetic sensibilities, moral intuitions and common sense. Why plead strict logical possibility when a Franciscan knowledge can supplement what would otherwise be a sterile analytical rationalism?

######

FrJDR writes: At the core of the story is the fact that the damned can leave hell for heaven at any time. Christ’s victory was to open the doors of paradise to the damned. If anyone remains, it is only because (as Lewis said in The Problem of Pain) “the doors of hell are locked on the inside.”

John’s response: If all perditionists subscribe to this vision of Christ’s victory, then that “hell” might more closely resemble a purgative state, possibly transitory? If they also subscribe to a universal hylomorphism, there could be no locked doors, inside or out.

######

FrJDR writes: I will end by adding one story alongside Lewis’s.

John’s response: Why must one’s conceptions of freedom, autonomy and the efficacy of grace be necessarily tied to a violent dichotomy between hating God, on one hand, and divine nuptial bliss, on the other? What’s incoherent about creation, incarnations and grace being peacefully & harmoniously ordered, rather, toward our journeys from abundance to superabundance, from divine images to likenesses, from friends to lovers, from enlightened self-interest to agapic self-emptying?

######

FrJDR writes: Universalism is Calvinism about salvation, only with a pretty face. But these beliefs that we are free in our choice to love God, and that God is free in his choices to love and redeem us, are central to Christianity’s story of salvation. Universalism has been definitively condemned as heretical for good reason: eliminating freedom from the picture leaves us with an unrecognizable vision of God and ourselves.

John’s response: Universalism, rather, is a robust Thomism, which has come to grips with its universalism problem to accept the implications of predestination, impeccability & inancaritability when properly coupled with zero beatific contingencies. What separates Báñezians, Molinists and certain Open Theists from Calvinism is – not just single vs double predestination, but – the fact that grace is non-necessitating.

######

Hell and the Coherence of Christian Hope By James Dominic Rooney November 29, 2022

FrJDR writes: All of this sounds nevertheless shallow and pitiful to those who cannot imagine any such reason.

John’s response: So far, so good.

######

FrJDR writes: No one . . . so long as he lives this mortal life, ought in regard to the sacred mystery of divine predestination, so far presume as to state with absolute certainty that he is among the number of the predestined …

John’s response: Because perdition does not refer in my universalism but predestination does, I should be clear that to me it refers to sainthood, degrees of holiness, beatitude and such. In that sense, no one should presume anything.

######

FrJDR writes: Rejoicing in the Cross makes little sense if there were nothing to be liberated from. If it were not possible for us to end up in eternal death, if Christ did not harrow hell, Easter is a sham victory, “our preaching is empty and your faith is also empty” (1 Cor 15:14).

John’s response: Without hell, there’s nothing from which to be liberated? Without hell, there would have been no incarnation? Contra Maximus and Scotus? Without hell, there would be no need for grace? Without hell, there’d be no need to trust God?

######

FrJDR writes: Problems of evil—such as the problem as to whether an all-good God can permit hell—argue that a certain instance of evil is incompatible with God’s goodness and conclude: “therefore, God does not exist” (or is not loving, etc.). But these arguments are logically unsound and invalid for the reason that an all-good, all-knowing, all-powerful God can have some good, justifying reason for allowing any given instance of evil. I might not know what it is, but, if some such reason is possible, there is simply no logical contradiction between God’s existence and any given evil, including the possibility that God permits us to reject his love forever.

John’s response: redux

Theological skepticism of the perditionist regarding the problem of hell and that of the theodicist regarding the problem of evil are invoking radically disproportional evils in their respective mysterian appeals, the latter evil being, although otherwise horrendous & incomprehensible, finite and transitory, the former infinite and everlasting.

######

FrJDR writes: From my perspective, we can always be more confident, as Christians, that God is good than of any evidence in favor of any instance of evil we see or experience being pointless or meaningless. So, if evil occurs, we can be confident that God has good reasons for permitting it. This point is not very strange or controversial, I think, as it formalizes the “hopeful” reasoning by which Christians respond to evils in their life:

John’s response: Perditionism, rather, formalizes the “hopelessness” of hell precisely because it is infinite and everlasting. It also makes a mysterian appeal that, rather than surpassing our fondest parental hopes, aesthetic sensibilities & moral intuitions with an unimaginable weight of eternal glories building on those connatural inclinations, overturns them by enshrining what’s parentally alien, aesthetically repugnant & morally unintelligible, absolutely foreign to what’s been implanted in our hearts.

######

FrJDR writes: When we have hope, we already expect that God’s goodness will shatter even the limits of our imagination, and that, even when things appear to be hopeless, they never are.

John’s response: I responded at the end of the first article: “If all perditionists subscribe to this vision of Christ’s victory, then that “hell” might more closely resemble a purgative state, possibly transitory? If they also subscribe to a universal hylomorphism, there could be no locked doors, inside or out.”

I’ll similarly observe, if all perditionists truly believe that, for the putatively damned, things are never hopeless, then their “hell” might more closely resemble a purgative state after all, possibly transitory?

######

Hard Universalism, Grace, and Creaturely Freedom By James Dominic Rooney January 17, 2023

FrJDR writes: For theologians like Hart, these implications are central to their views of creation, redemption, universal salvation, and grace.[1] Claims that God cannot but create and raise us to grace imply an essential relationship between God and creation. If God could do nothing other than create or redeem us, given what he is, we would be essentially related to him, which is the basis from which Hart concludes that all must be saved.

John’s response: This entire article caricatures both Hart & Wood.

The Christologies and cosmologies of JDW & DBH can be roughly mapped to Joe Bracken’s creatio ex Deo.

For all of them, the hypostatic union is fitting (not necessary), creation’s gratuitous, the analogy of being holds & the potencies of human nature are relative perfections. Ergo, human persons enjoy their primary beatitude, finitely, as adoptees.

Confusion often ensues from mistaking essential & personal logics. JDW’s personal logic, informed by Maximian & Neo-Chalcedonian elements, differs somewhat from DBH’s personal logic, informed by Bulgakov’s Sophiology.

While those logics go beyond the analogia, they don’t go without it.

I commend the work of Brandon Gallaher, who uses Bracken to correct Bulgakov’s infelicities. Bracken, himself, engages Hegel, German idealists & Peirce, but he tames their insights with certain neoclassical commitments.

The personal logics of Bracken, JDW & DBH roughly converge on the same Totus Christus conception of mutually constituted I – Thous. These logics aren’t drastically different from the personalist account of Norris Clarke or from Don Gelpi’s metaphysic of intersubjectivity.

Fr. Bracken and the late Frs. Clarke & Gelpi are all FrJDR’s co-religionists. Jesuits are just smarter than Domnicans, I’ve found.

The universalisms of JDW & DBH don’t follow, explicitly or by implication, directly or indirectly, from rejections of either the analogy of being or the gratuity of creation. They follow, rather, from applying the Anselmian principle to the Trinitarian missio ad extra:

Potuit, decuit, ergo fecit: ‘twas possible & “fitting,” ergo accomplished. They also follow from moral intuitions grown from the special revelation of Who Abba is & How Abba acts as manifest in Jesus.

They don’t deny the gratuity of grace either as it gifts us a superabundance beyond abundance, a divine intimacy beyond friendship, just not a morally unintelligible dichotomy between hating God and divine nuptial bliss.

######

FrJDR writes: All these claims, however, are strictly metaphysical nonsense.

John’s response: Well, the caricatures are indeed nonsense.

######

FrJDR writes: God’s own reasons are not naturally accessible to us; we cannot deduce what God will do and what goods he could bring about that might be sufficient to defeat the badness obviously involved in hell.

John’s response: Again, the skeptical theisms used by perditionists and theodicists in their defenses of hell and evil involve wildly disproportionate mysterian appeals.

######

FrJDR writes: To disprove the view that it is impossible for anyone to go to hell, we only need to show that what God achieves by permitting hell could be worth the mere possibility.

John’s response:

Moral.

Modal.

Collapse.

Permission tantamount to intention.

######

FrJDR shares his noseeum inference: And I see no good reason that there is nothing God could achieve that would not be able to defeat that badness of hell’s mere possibility.

John’s response:

The Coherencies of Indicative Universalism – the universalist weseeum inference

https://syncretisticcatholicism.wordpress.com/2023/06/06/the-coherencies-of-indicative-universalism/

######

Please also see:

Why Beatific Contingency is an Oxymoron – about our divine indwelling

Parallels between Logical & Evidential Problems of Evil & of Hell

The Full Maximian Apokatastases Monty: immortality, theotic realization & apokatastenai

a storyboard regarding the “hows” of apokatastenai

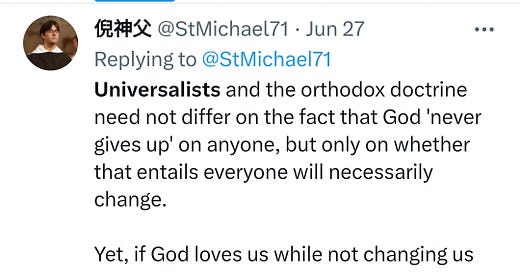

Examples

Stipulations:

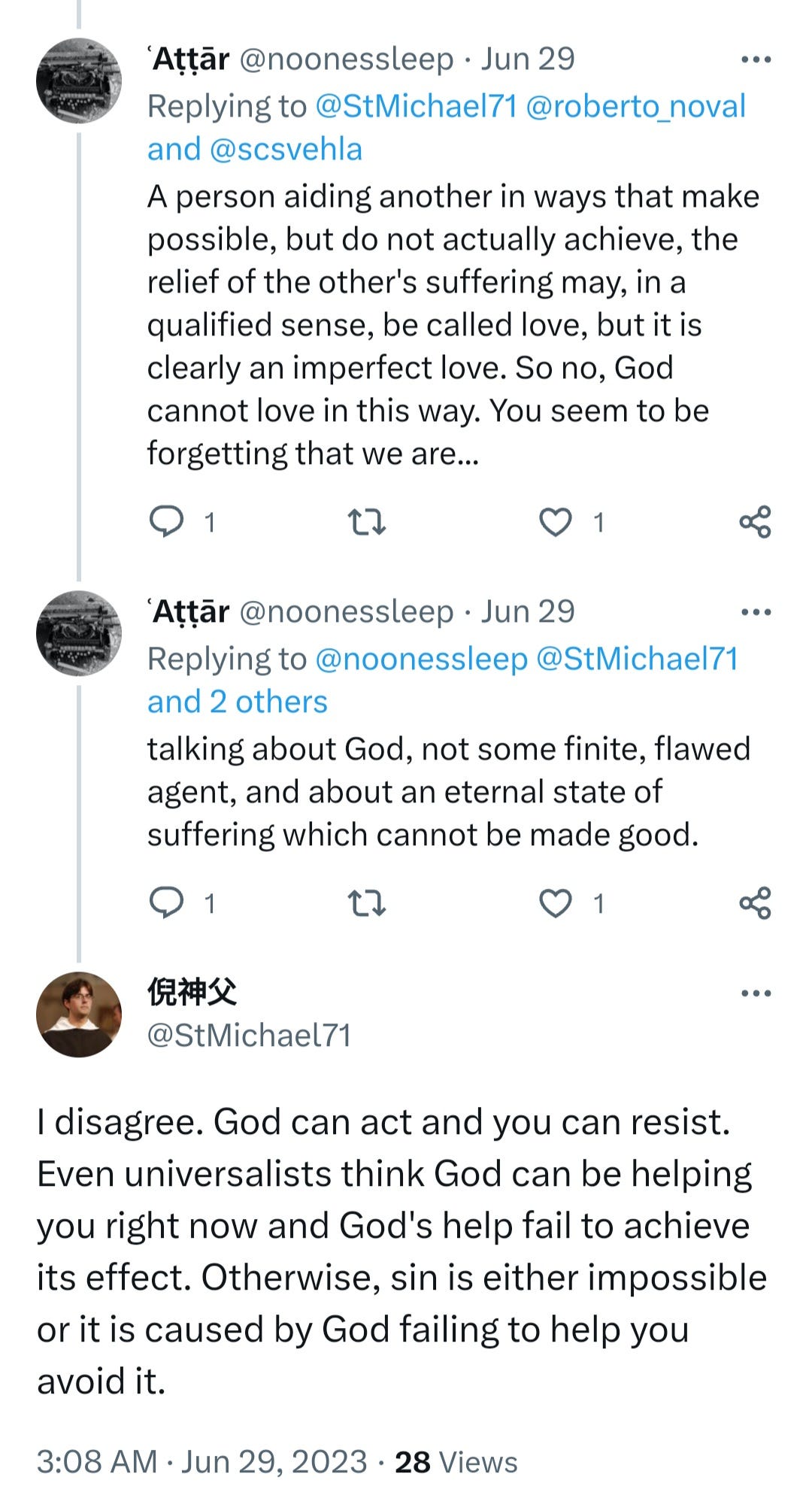

Sin is possible.

It is not caused by God failing to help us.

God can act and we are free to say no.

God can be helping us right now and God’s help can fail to achieve its affect.

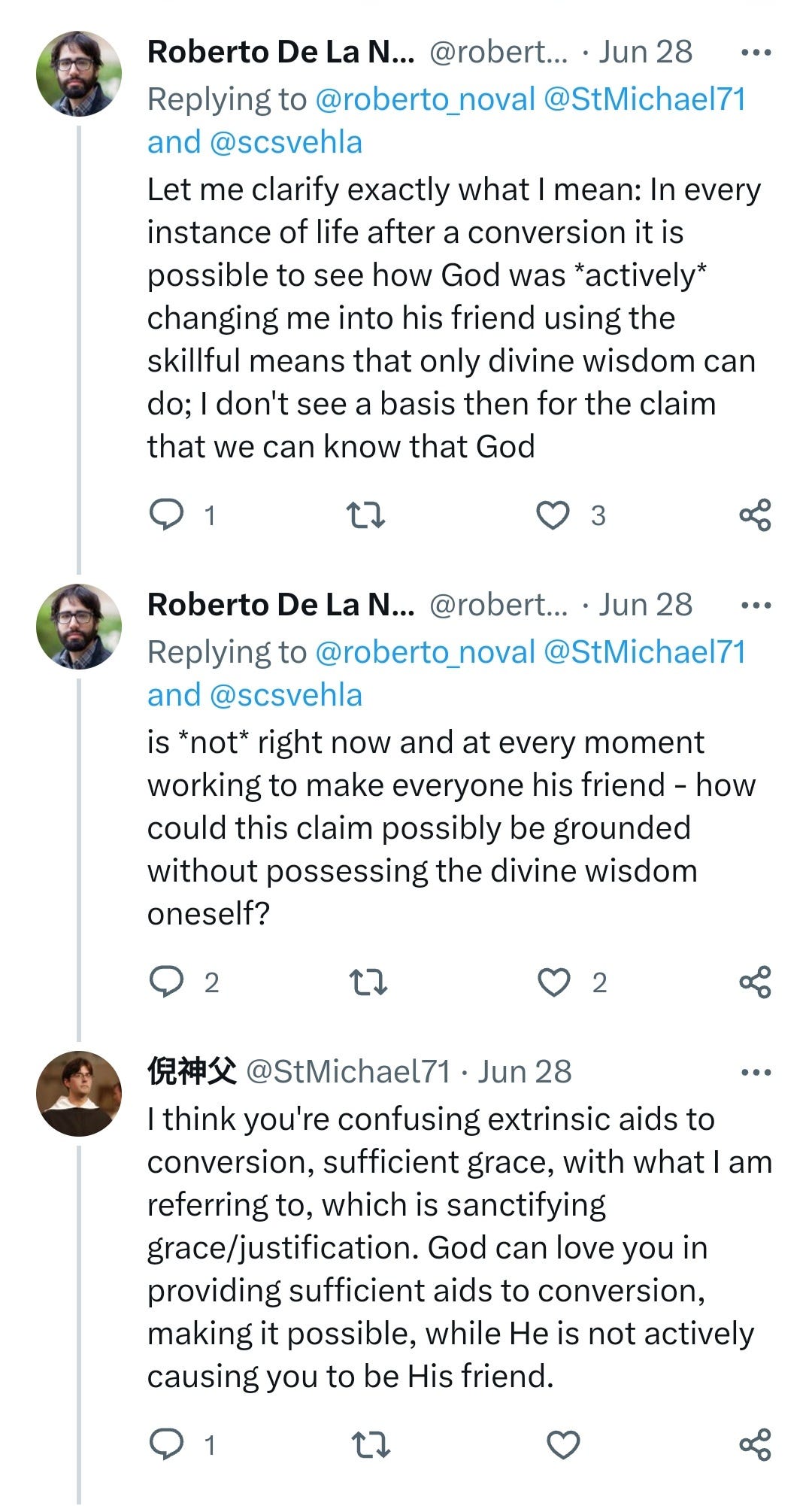

God can love you in providing sufficient aids to conversion, making it possible, while He is not actively causing you to be his friend.

If God can love us while we are sinners today, He can do that any time.

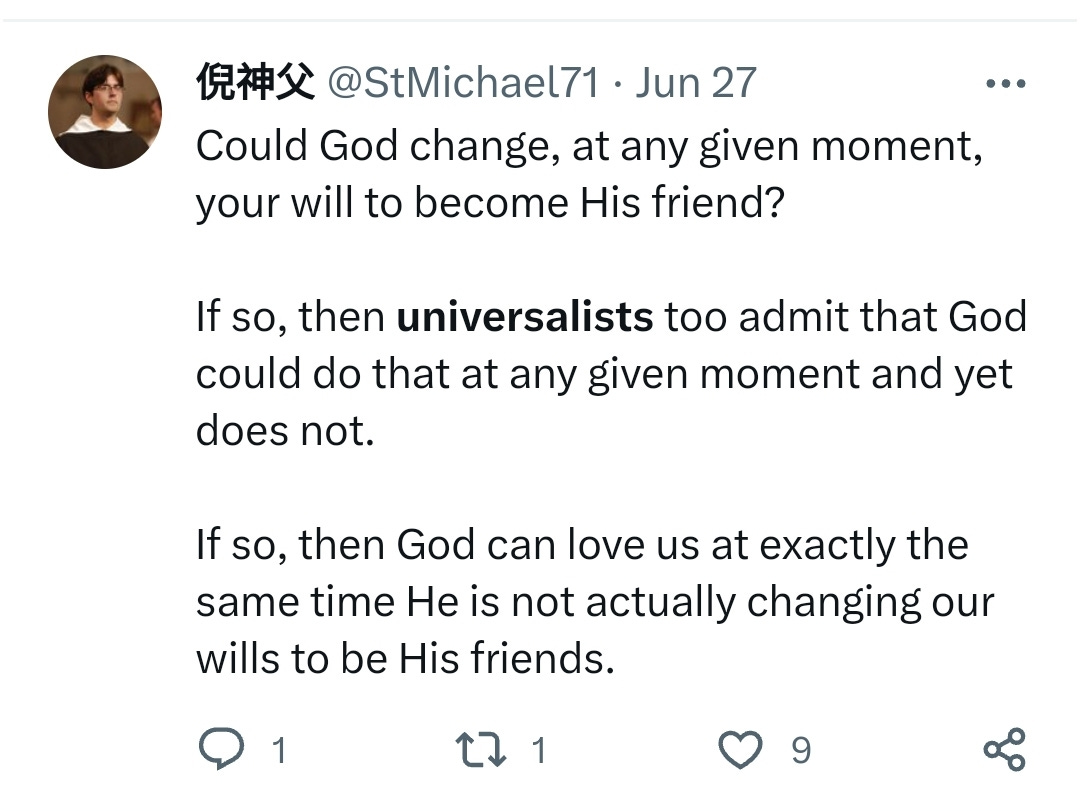

God could, at any moment, infallibly procure our consent to become His friend. He could do that at any moment yet does not. God can love us at exactly the same time He is not infallibly procuring our consent to be His friend.

God never gives up on anyone.

If God loves us while not changing us necessarily, it doesn’t follow from that that all necessarily change.

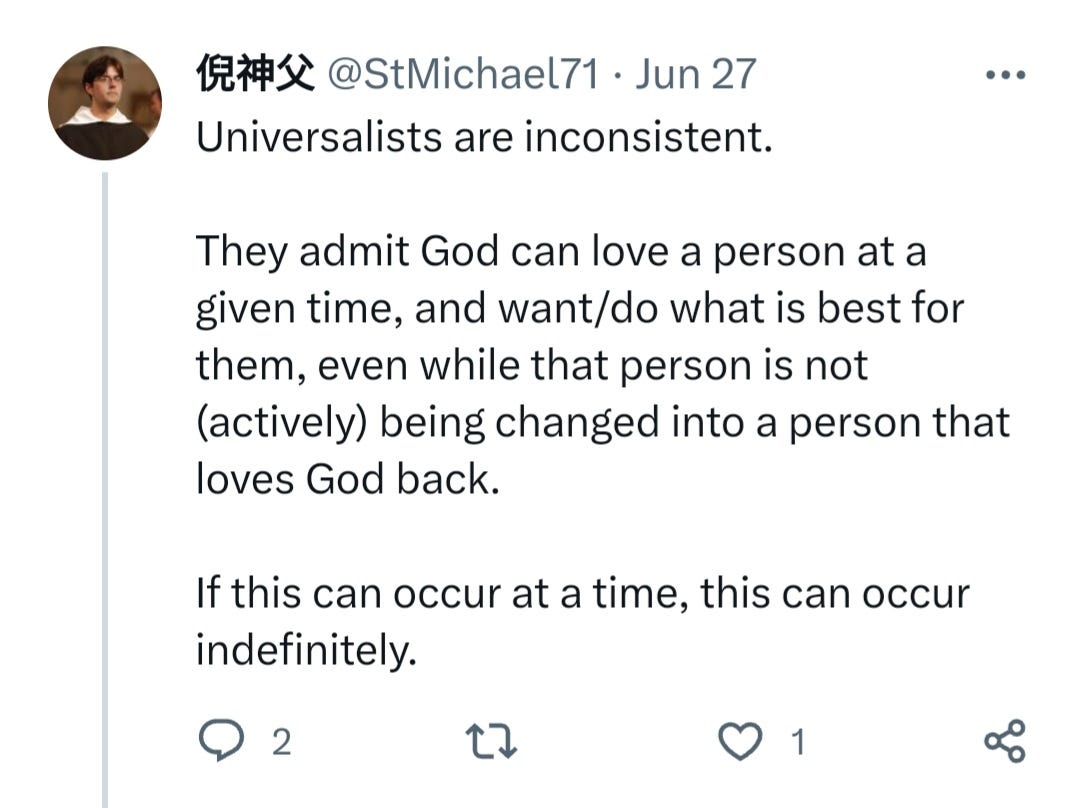

God can love a person at any time and want to do what’s best for them, even while that person’s consent to love God back is not infallibly being procured.

If this can occur at any time, can it occur indefinitely?

No, not to the extent it would involve any indefinite deprivations of our original beatitudes & teloi. Regarding higher degrees of beatitude & glory, our divine intimacy might indeed grow indefinitely.

God, fittingly (not necessarily) in being true to Himself (His loving will manifesting His loving nature), would (as distinguished from metaphysical terms like could) not indefinitely deprive any rational creature of her original beatitude or his original teloi or even leave anyone, post-mortem, peccable.

If necessary, then, God will, fittingly, infallibly procure our consent to, at least, love God for our own sake as our sole Benefactor. He may also infallibly procure the consent of some to be His friends & of others to even be His lovers.

Without a sufficient knowledge of God, a finite creature could not definitively reject God.

With a sufficient knowledge of God, a finite rational creature would be gifted, along with impeccability, at least a love of God for sake of self.

Divine punishments that would permit such eternal consequences for finite creatures are prima facie disproportionate.

God would not be good if he allowed even the possibility of such disproportionate consequences.

A truly efficacious grace is infallibly followed by the act to which it tends, e.g. contrition. Even before one’s will consents to it, that grace, infallibly sure of success, will infallibly procure one’s consent, produce that act – of contrition. While it infallibly procures one’s consent, it doesn’t necessitate consent, instead leaving one free to dissent. The will will infallibly say “yes” to it, but it is free to say “no.”